Of all of the articles on Piano Price Point, I find this one the most compelling, the most interesting and the most transformative. A man named Jack Brand, third generation felt maker from Germany, owns a company that manufactures piano hammer felt for the world’s top brands. He tells us the story of how the secret felt “recipe” was lost in World War II and didn’t re-appear until 1990. This story is significant because the hammers on any piano mark the tone of the instrument. Having lost this recipe during the war meant that pianos would never be the same. In fact, many people have wondered why the pre-war pianos were considered the “golden era”. In part, it was due to this felt, this recipe. The strike of the hammer to the string determines the colour, the characteristic, the depth, the attack and the softness of tone. Jack runs the oldest, most respected felt company in the world. I’m so excited to share his words. I’ve only scratched the surface and already I’m finding that in addition to having the secret formula, felt making requires dedication to art and intuition of working with felt fibres. Established in 1783, Weickert is over 230 years old! The trade secrets, production notes, and piano technician feedback have been handed down so that this closely guarded secret of felt making lives on. But don’t take my word for it… let’s hear it from Jack.

Of all of the articles on Piano Price Point, I find this one the most compelling, the most interesting and the most transformative. A man named Jack Brand, third generation felt maker from Germany, owns a company that manufactures piano hammer felt for the world’s top brands. He tells us the story of how the secret felt “recipe” was lost in World War II and didn’t re-appear until 1990. This story is significant because the hammers on any piano mark the tone of the instrument. Having lost this recipe during the war meant that pianos would never be the same. In fact, many people have wondered why the pre-war pianos were considered the “golden era”. In part, it was due to this felt, this recipe. The strike of the hammer to the string determines the colour, the characteristic, the depth, the attack and the softness of tone. Jack runs the oldest, most respected felt company in the world. I’m so excited to share his words. I’ve only scratched the surface and already I’m finding that in addition to having the secret formula, felt making requires dedication to art and intuition of working with felt fibres. Established in 1783, Weickert is over 230 years old! The trade secrets, production notes, and piano technician feedback have been handed down so that this closely guarded secret of felt making lives on. But don’t take my word for it… let’s hear it from Jack.

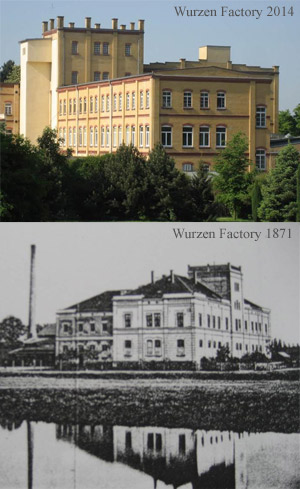

Weickert and Wurzen are some of the oldest names (THE oldest??) for felt manufacturing in the world and yet the Weickert felt has been “re-introduced” again for hammer manufacturing, correct? Can you tell us a little history about the name and origins as well as your involvement with Weickert and Wurzen?

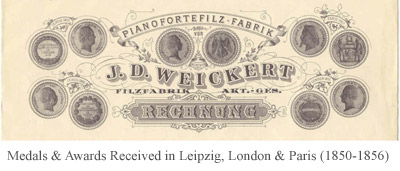

Wurzen is the oldest existing felt plant of wet processed felts in the World. The oldest. Basically, I was very lucky to come across this beautiful opportunity to re-introduce the old legendary Weickert Felt. All the know-how had disappeared between 1945 and 1991.The Weickert company was expropriated in 1945 by the Communist government and the family fled to the West. The last owner of the company was Alice Weickert, who was an American and had married into the Weickert family. Steinway New York was one of the largest US customers for Weickert hammer felt. I am the fourth generation of textile makers, third as felt makers in the Brand family. All previous generations lost everything due to wars and expropriations, my dad and mom started in the West with nothing after WW2. I am the first in four generations who can build on something.

Wurzen is the oldest existing felt plant of wet processed felts in the World. The oldest. Basically, I was very lucky to come across this beautiful opportunity to re-introduce the old legendary Weickert Felt. All the know-how had disappeared between 1945 and 1991.The Weickert company was expropriated in 1945 by the Communist government and the family fled to the West. The last owner of the company was Alice Weickert, who was an American and had married into the Weickert family. Steinway New York was one of the largest US customers for Weickert hammer felt. I am the fourth generation of textile makers, third as felt makers in the Brand family. All previous generations lost everything due to wars and expropriations, my dad and mom started in the West with nothing after WW2. I am the first in four generations who can build on something.

In 1991 my dad asked me if I was interested in coming back to Germany to look at my grandfather’s plant which couldn’t be salvaged and also at the former Weickert felt plant.

To make a long story short, my dad and I re-privatized the old Weickert plant in 1991. We got a phone call from Renner, Germany asking us whether we could produce the old Weickert felt. We were lucky, the old production recipes were handed to me by an old former production manager of Weickert’s.

Unbelievable! Through the turmoil of bombed out factories in the war, the recipe disappearing for approximately 50 years, it then resurfaces in the late 80’s. I can’t even imagine how different the piano world would be today had this one simple formula had not changed hands.

Precisely. And so with this new-found formula, we ran some materials and the hammers were sent anonymously to Steinway. The response from Steinway (who did not know who had made the felt) was:

– this felt reminds us of the old Weickert Felt

– where is this felt company?

– and can we get more?

The rest is history. The PTG (Piano Technician’s Guild) of Germany came to the Wurzen plant in 1992, and conducted blind tests on four different grands and the difference in tonal result was significant. After that our supply for Wurzen/Weickert hammer felt was always sold out. Capacity has steadily increased to the point where today annually 180,000 to 200,000 instruments are outfitted with Wurzen felt, about the same amount as in 1903 when ‘Weickert’ felt already had a widely recognized name in the piano world.

Your company Brandfelt.com – how did you get into this business? Did you grow up always wanting to manufacture felt?

I basically learnt felt around the breakfast and dinner table. Our living quarters were at the felt plant. My parents sent me to Canada in 1971 because they wanted me to grow up in a country where there hopefully would not be wars. A small felt plant was founded in Toronto, something to fall back on, in case everything gets lost again thru political turmoil.

Personally I am a production/product development guy who identifies with a natural product like wool felt and who got lucky to stumble upon the challenge of piano felts, which is probably the most difficult felt to make. My colleagues and I didn’t invent the Weickert hammerfelt production method, we only re-introduced it because of fortunate circumstances together with determination and real interest in the product by a whole bunch of people in our factory. At this point I also want to thank all the piano builders and hammerhead makers in the world who showed genuine interest in making a better product and let results speak for themselves.

Piano felt is a small part of our overall world sales, but it is one of the most challenging and interesting ones. We have manufacturing and converting plants in USA, Canada, Europe and Far East.

Let’s get into hammer felt making. How many basic grades of felt are there?

First of all I would say there are today about four major different manufacturing methods in the world for piano hammer felt.

1) I call it the Royal George method out of England, whose technology was purchased by a Japanese felt company in the early 90s,just as the Wurzen /Weickert hammer felt method was being reintroduced into the market place. Royal George as a felt maker does not exist anymore.

2) The VFG method which is a manufacturer out of Germany (in the former West Germany before German reunification in 1989).

3) The Japanese/Chinese method which existed before a Japanese felt company purchased the know how from Royal George, England.

4) The Weickert/Wurzen method which was developed in 1847 near Leipzig and which by 1861 was internationally recognized. By the early 1900 ‘s the J.D. Weickert Piano Forte Felt Company supplied top hammer felt for about 200,000 annually world wide.

Each of these felt methods provide different resiliency or elasticity effects in the felt, hence different results at the hammer head maker and different tones at the voicing stage (because each type of felt will react different in voicing even if hammerhead making method, voicing method and type of instrument are the same)

Each felt manufacturer offers in addition different grades. The Wurzen Felt company offers 4 different grades:

-Piano (which can also be used for grand instruments)

-Grand A

-Grand AA

-Weickert Special (the latest and probably also the best in most instances, especially for grand instruments)

All these four different grades by Wurzen are being produced in accordance with the basic principles of the legendary Weickert hammerfelt manufacturing method. The difference in the above felt grades can, for example mean different wool blends and/or slightly changed processes, for example with more or less hand labour in the different stages of production. But we always follow the old Weickert method which nobody else does in the world at the moment. Basically the different grades offer different kinds of elasticities to the hammerhead maker and end user. Weickert in the olden days also carried four different grades of top hammer felt.

What exactly is virgin wool? I presume it doesn’t refer to non-promiscuous sheep…hahaa Do piano hammers primarily use virgin wool?

Virgin wool is wool shorn from live sheep, not dead sheep (usually raised for meat production. Those wools are called skin wools which often are chemically removed). Usually live animals get shorn twice or once a year depending on the food environment and what type of length or fineness of fibre is required. These are virgin wools.

So the big question: What raw materials and process make for great piano felt? What factors affect tone?

Using the right fibres is very important and a prerequisite. The Wurzen/Weickert felt company has a long tradition of knowing what fibres are best suited and how these fibres have to be processed after they are shorn from the sheep. We have our own company specific recipes and specifications, which we consider proprietary. But the different steps in the manufacturing method are essential to provide good tone results in the end (fibre blend, mixing, carding, felting, fulling, finishing). This is where the real know how lies and which differentiates the Wurzen/Weickert felt from all other methods in the world.

In my seminar on the principles of felt making I hand out identical pairs of felt samples which represent the different stages of production, i.e. felted or fulled material but which feel quite different from one another in your hand when you squeeze, bend or just touch them. The pairs of samples are identical in fibre, dimensions and weight and still one will feel harder or stiffer than the other (or one surface feels smoother and the other rougher). Why the difference? Well it is the difference in production method. For example the one sample may have been exposed to high temperature steam whereas the other to low temperature steam affecting the moisture content in the felting and interlocking of fibres process (for fibres to interlock properly the scales on the fibres have to properly open up before they can interlock which only happens if you have the right temperature and moisture content),the right stoke and speed settings of the felting plates, plate patterns, type of transportation cloth on which the material gets felted, etc…

In my seminar on the principles of felt making I hand out identical pairs of felt samples which represent the different stages of production, i.e. felted or fulled material but which feel quite different from one another in your hand when you squeeze, bend or just touch them. The pairs of samples are identical in fibre, dimensions and weight and still one will feel harder or stiffer than the other (or one surface feels smoother and the other rougher). Why the difference? Well it is the difference in production method. For example the one sample may have been exposed to high temperature steam whereas the other to low temperature steam affecting the moisture content in the felting and interlocking of fibres process (for fibres to interlock properly the scales on the fibres have to properly open up before they can interlock which only happens if you have the right temperature and moisture content),the right stoke and speed settings of the felting plates, plate patterns, type of transportation cloth on which the material gets felted, etc…

The point is the resiliency/elasticity of the product always changes if one changes any of the parameters in the production process. So that is the craftsmanship which one has to attain thru a lot of trials and errors. Specs of weight and dimension and which fibres alone don’t define the elasticity of hammer felt. One needs to know how these wool fibres are being processed under what parameters at each step of the production process.

The end result is a certain felt elasticity which stands for, in our case, for the Weickert method of hammer felt making. Generations of felt makers at our plant in Wurzen developed it in conjunction with and with feedback from piano builders and hammerhead makers since 1847. The Weickert method is proven and with the help of a good hammer head maker who will adjust his method to our felt, it will produce a beautiful tone. It is very important to work closely with a hammer head maker and also with the piano builder or piano technician to get optimal results. You can have great felt but without the right hammer making method you will end up with mediocre results. Vice versa a good hammerhead maker who knows his stuff and uses a mediocre piece of felt can still get a decent result but not the optimal one.

We know of many examples where the identical Wurzen felt hammer specification was made into hammers by different hammerhead makers for the same piano factory customer, one was good and the other was rejected. The conclusion is that without all three parties working closely together (felt maker, hammer maker, piano builder) you almost have no chance to get the optimal tone result.

To answer your question ‘what affects tone’ I would say it is almost endless but it helps to know what felt and which grade is on your hammer,who made the hammer and what method was used (ie hand vs Hydraulic press, prepress or not, shape of how felt is cut from sheet, what temperatures and times in presses etc…) and what design of instrument and tonal taste one wants to achieve.

The art and science behind felt making, the experimentation, the feedback from builders and technicians – it’s amazing that the Weickert “secret recipe” was not lost. Pianos around the world might have been changed forever had these production notes not have been found and handed to you.

Yes! The basic trade secrets were handed over to me by the then production manager in 1991 who in turn got it from the previous production manager who was still working during the Weickert family era. The last production adjustment to the Grand D hammerfelt spec production sheet for Steinway was initialled and dated in 1933.

Wow! That’s incredible. For those wanting to see felt making in action, here’s a video link to the Brand Felt Company in Canada. I’ve learned so much about an area of pianos I knew so little. And scratching the surface one quickly realizes how broad this speciality is. I just want to convey my thanks to Jack for taking the time to do this interview. Your insights and expertise are not only helpful but inspiring and captivating.

More Piano Articles

During the performance of Jacob Collier at the most recent NAMM show I was reminded that music makes us human, that beauty binds us together as a collective, and that the reason the music industry exists is to aid in the creation of art. I needed that reminder without which, the annual trade show featuring many of the great piano makers is just the sale of wares. I believe that people are feeling the uncertainty ...

I used to have a teacher who would frequently say, “For every single grade point PAST 80%, it takes as much effort as the FIRST 80.” I believe this statement to be true from experience. The first 80 is the easiest. Chipping away at every point past that is the challenge. The bulk of the work can bring a project into shape but it’s the pursuit of excellence, that’s where the challenge lies. Yamaha is ...

The value of a piano is obvious ~ it’s the music that you make with it. But often, families are going through life changes which involve a house move and unfortunately, the piano needs to be sold. They invariably ask the question, “What are we going to do about the piano?” This question comes up because, as you can imagine, they’re not easy to move. We don’t simply pack them away in a cardboard box ...

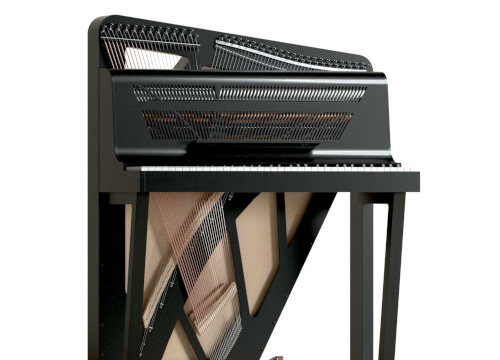

You’ve been playing your piano for years now and the time has come to seriously consider downsizing the house and move into a condo. But what do you do with the piano? You love your piano and can’t imagine life without it and besides, you absolutely hate the idea of playing a digital keyboard. Many people don’t know that you can add digital functionality without compromising your existing piano. Yes, it is completely possible to ...

Many years ago, I remember seeing a piano in a museum similar to the one shown above (built in 1787 by Christian Gottlob Hubert. On display at Germanisches Nationalmuseum - Nuremberg, Germany). I have often wondered why acoustic portable pianos never really took off. Although we've seen more portable keyboard instruments like harpsichords, accordions or electronic keyboards, they operate completely different from a traditional piano in that they either pluck the strings, use air with ...

This was the first year since covid that the National Association of Music Merchants (NAMM) trade show was back to its regular January date and, in fact the first show where it felt back to normal. How was it? To answer that, I'm going quickly review the piano market over the last few years. Piano sales boomed during covid. Think about it - everyone was at home and with time on their hands, many turned ...